Crowds gathered in Springfield, Illinois, on May 4, 155 years ago to lay Abraham Lincoln to rest following the last funeral to be held as his body made its journey home from Washington, D.C. To all those who knew that the late President loved dogs, it might come as no surprise that a dog would be present at Lincoln’s Springfield home for the occasion.

Not only did Lincoln love dogs, they seemed to love him in return. Stories of his companionship with dogs span Lincoln’s life from his youth to his presidency. As a young man moving west to Illinois, he saved his small dog from drowning in an icy creek. At Springfield, stray dogs, and cats too, found comfort and care at the Lincoln family’s home. Perhaps his famous dog Fido was one of these. In Washington, a dog once followed Lincoln home to the White House.

Not only did Lincoln love dogs, they seemed to love him in return. Stories of his companionship with dogs span Lincoln’s life from his youth to his presidency. As a young man moving west to Illinois, he saved his small dog from drowning in an icy creek. At Springfield, stray dogs, and cats too, found comfort and care at the Lincoln family’s home. Perhaps his famous dog Fido was one of these. In Washington, a dog once followed Lincoln home to the White House.

It seems fitting that a man who loved dogs so well should be accompanied by dogs even in death. On at least three occasions, dogs were present at funeral ceremonies or viewings held after Lincoln’s assassination.

Fido was a well-known figure in Springfield, where he had lived with the Lincolns for about six years, frequently accompanying the future president around town. He would wait for his master outside the barber shop, and often carried papers for him as the two walked along.

When the Lincolns left for Washington in 1861, Fido remained behind with the family of John Roll, whose boys were friends of the Lincolns’ sons. Concerned that Fido would be fearful and unhappy with the bustle of Washington, the Lincolns had arranged for the Rolls to care for him. They specified that Fido could not be tied up alone in the yard, must be allowed in the house whenever he asked to come in, and allowed in the dining room at mealtime. To help Fido feel at home, the Lincolns gave the Rolls the dog’s favorite horsehair sofa.

When Springfield held Lincoln’s funeral on May 4, visitors flocked to the Lincoln home. John Roll took Fido there as well. It is also possible–perhaps even likely*–that on this occasion he also took Fido to the photography studio of Springfield photographer F.W. Ingmire. Cartes de visite of the yellow dog became popular keepsakes connected with Lincoln’s funeral.

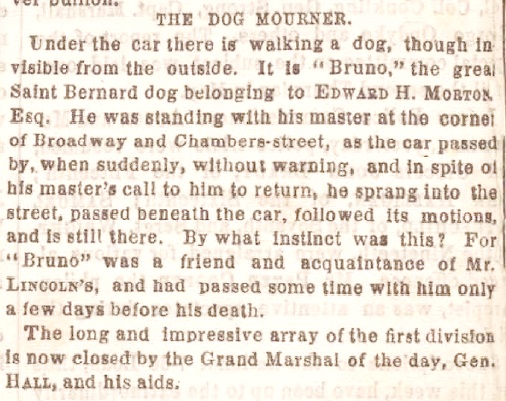

Days earlier, in New York City, another dog who also knew Lincoln took part in meeting his casket when it arrived by train. The New York Times reported on the episode in its April 28, 1865, edition:

On the day that Lincoln’s casket reached Indianapolis, heavy rains curtailed plans for a procession to the Statehouse, where Lincoln would lie in state. Instead, his casket was quickly transported, preventing a public gathering at an elaborate building that had been erected as an archway and memorial exhibition hall. But event organizers would not allow their tribute to be missed. The next day, a crowd assembled at the arch for photographs, with a substitute casket in the hearse.

A photograph taken that day is in the collection of the Lincoln Financial Foundation at the Allen County Public Library in Fort Wayne, and can be seen here. Zooming in on the photo reveals one small figure in a prominent position directly beneath the front of the hearse. Behind its front wheels stands a small dog, facing away from the camera.

If the dog looks familiar, it may be because of his remarkable resemblance to another dog who had been present during Lincoln’s historic visit to Gettysburg on November 19, 1863. The Indianapolis dog, with his short legs and distinctive white ruff of fur at the base of his neck, looks much like the dog who stood with the crowd watching the procession that filed through Gettysburg’s streets to the dedication of Soldiers’ National Cemetery.

Close-up of a dog in the crowd at Gettysburg, November 19, 1863

The small dog at Gettysburg appears at the center of this view along Baltimore Street. https://www.loc.gov/item/2012647717/

Like that little dog of Gettysburg, these three–the Indianapolis dog, Bruno, and Fido–all were witnesses to history. And, as dogs, ever keen to perceive human emotion, maybe they too felt the solemnity of the events they witnessed.

For Further Reading: “Twenty Days: A Narrative in Text and Pictures of the Assassination of Abraham Lincoln and the Twenty Days and Nights that followed—The Nation in Mourning, the Long Trip Home to Springfield,” by Dorothy Meserve Kunhardt and Philip B. Kunhardt Jr.